Before I loved movies, I loved superheroes. Growing up without the organizing principle of a cinematic universe or the obsessive completionism of a weird adult, I drifted across whatever continuities and characters caught my fancy. Comics could still be plucked off dollar racks at a gas station, meaning as a curious 8 year old I could enjoy an issue of Spawn and Sonic the Hedgehog over the same car ride. When I got home I could sink into the couch, turn on the TV, and fill my brain with visions of bright colors and cartoon violence, from Captain Planet to Batman Beyond, broadcast across the golden age of cable and rentable on VHS and DVD. When Sam Raimi’s PG-13 Spider-Man was released in 2002, my dad bought me a bootleg tape to be enjoyed in the safety of our home. I more or less didn’t notice, but the author of this bootleg had just walked into a movie theater, snagged a good seat, and filmed the projection straight to his camcorder. I will always associate Sam Raimi’s rendition of spidey-sense—in which Tobey Maguire’s Peter Parker detects a spitball in slow motion—as being accompanied by an opening weekend audience’s chorus of “eeeeewwww!”

Superheroes have become so culturally omnipresent that it is difficult to write about my relationship to them without feeling like I’m sinking into a vat of acid cringe. Vera Drew proves that from this toxic waste great jokers can emerge. The People’s Joker is about a closeted trans girl who moves from the midwest to Gotham City to get her start in standup, only to find that Batman and Lorne Michaels rule the city with an iron first, outlawing all comedy not performed through the United Clown Bureau. She starts an anti-comedy troupe with her best friend Oswald Cobblepot (played by a heroically funny Nathan Faustyn), falls in love with Mr. J (a trans guy with “Damaged” tattooed across his forehead), and develops an act as Joker the Harlequin, which quickly becomes far more than just a drag persona. It is a memoiristic comicbook satire about building an identity out of the detritus of a cultural wasteland, where the chaotic expanse of superhero storytelling has been monopolized by corporate behemoths looking to crush narrative deviance in the name of brand consistency. Of course, this is precisely what happened in real life, when disgruntled lawyers from Warner Brothers decided to throw their weight around the night before the film’s premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. This angry letter scared off big distributors and delayed the release of the film. Picked up by punky queer label Altered Innocence, the film is now enjoying a hand tailored release across the U.S. where (one corporate parent later) it has been unbothered by the Warner Brothers legal department.

I first watched The People’s Joker in a packed cinema at the GAZE International LGBTQ+ Festival in 2023. It had been scheduled for the 2022 festival, before being pulled courtesy of Warner Brothers’ dick swinging. Any interest I had in the film was, of course, immediately magnified. One year later, I walked out of the rescheduled screening feeling like I was floating. I remember bumping into a fellow trans filmmaker and we both agreed it made us feel how other people said they felt about Everything Everywhere All At Once. While we quickly clarified to each other that referring to it as the “trans Everything Everywhere All At Once” was probably problematic, the thrill of genre maximalism sculpted around honest emotional catharsis was revelatory. It was seeing yourself on screen, but not just because it was created and starring a trans woman. It was a trans way of making a movie, unlike any we had seen before.

It was, embarrassingly, not dissimilar to how I felt watching The Avengers in 2012. In the ten years since bootleg Spider-Man had rocked my world, I had marched out to the movie theater for almost every major superhero release, but the concept of an interconnected universe felt like a new test for the moviegoing public. Would the normies go for the kind of storytelling that was the bedrock of my fantasies? Before I even watched it, I remember scrolling through Rotten Tomatoes, rooting for people to like it, rooting for this product of the Walt Disney Corporation to make a billion dollars. By the time I was sat in my seat at the local Regal, watching Joss Whedon spin the camera around the Hulk, Iron Man, Captain America, Thor, Black Widow, and Hawkeye, I could viscerally feel what the box office returns would confirm: the movie landscape had changed. Superheroes no longer needed madcap auteurs to convince audiences they were worth spending time on. A cast of supremely charming performers and the same humanist style that once made a group of vampire slaying teens feel like my best friends convinced the world that superheroes were just like us. Long after Whedon left the franchise, the MCU utilized his sensibility to clean up the experience of the superhero into tonally consistent tentpoles that go down easy.

Vera Drew animates her universe with the same kaleidoscopic chaos spirit that drew me to these stories as a kid. Live action footage shot over just six days is frizzed up with a cascade of animation styles aping everything from the 90s Batman cartoon to PS2 footage to Grant Morrison-style graphic illustration to South Park to puppetry. If you shouted the word “SUPERHERO!” at 8-year-old-me, then opened up my brain, only then would you experience a visual equivalent to The People’s Joker. Heroes and villains are not fixed characters but chimeras, shifting styles and tones to suit the emotional needs of the story and create a sense of play. Beyond providing my internet-addled brain with a whole new level of stimulation, Vera’s style is perfect for a genre that is so often acted out in playgrounds and backyards. If Marvel and DC produce adolescent fantasies with grown-up filters on top, Vera Drew captures what it was like to make your action figures fuck. It’s getting increasingly difficult to take seriously the stakes of characters like Ant-Man or The Flash, and The People’s Joker succeeds by reminding us that these characters are, first and foremost, silly fantasies. Rather than resuscitating the superhero, the film’s premise assumes they are already dead.

It wasn’t until remarkably recently that it felt like the superhero machine could fail. For the longest time post-Avengers, there was a sense that the Feige-brain trust was one step ahead of critics. When the naysayers were just beginning to accuse Marvel movies of being samey rehashes of beloved properties, they bet on a title about a talking raccoon and his tree best friend and it became a franchise hegemon. When they were written off as substanceless entertainment, Marvel picked then-internet-boyfriend Taika Waititi to direct Thor: Ragnarok, which any liberal arts undergrad was likely to explain to you was a clever metaphor for the legacy of imperialism. Less than 3 months later, Black Panther came out. I remember seeing Captain America: Civil War and cheering for the introduction of Tom Holland’s Spider-Man like it was a military victory over a rebel state. Glorious Marvel was annexing another beloved property for the fatherland. While there’s always been built-in competition between the Marvel and DC brands, the MCU did a remarkable job of taking burgeoning little leftist Bernie voters and making them corporate loyalists. The People’s Joker expresses more affection for the vast canon of its characters than any big budget superhero movie, all while constantly thumbing its nose at the capitalists who control them.

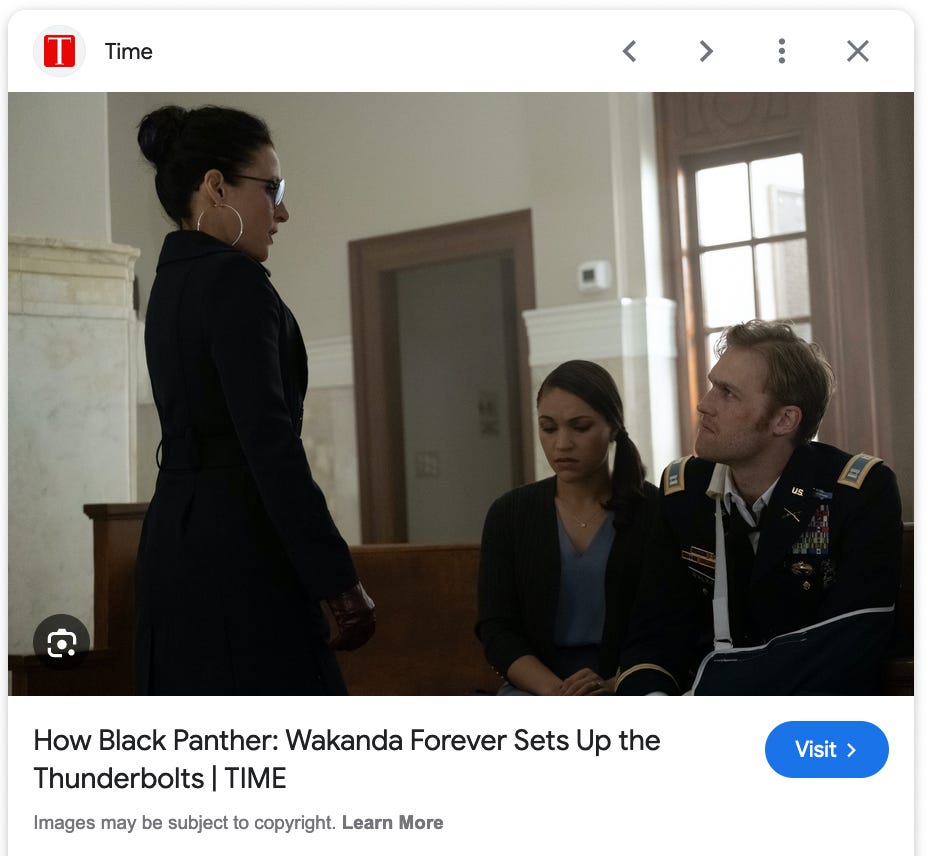

As late as 2022, I remember a friend of mine (who loves superheroes even more than I do), suggesting that the MCU was more than just a chapter of Hollywood history; It was the new mode of popular movies. What triggered this conversation was the teaser trailer for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. Two years after the tragic loss of Chadwick Boseman, the needle drop transition between “No Woman, No Cry” and Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright”, convinced us briefly that the Feige dream factory could do the impossible; Make it all feel okay. If the MCU could triumph over death, is there anything that could stop it? I wouldn’t call the resulting film bad, but all of its failings are symptomatic of the cinematic universe phenomenon as a whole. New characters are introduced with the sole purpose of setting up future wings of the franchise, old characters are brought back for all the True Fans who watched the TV show I didn’t give a shit about. Worst of all, the final product feels rushed, retrofitting a storyline built around Boseman’s T’Challa to a world defined by his absence. Making a film about the death of a beloved actor also the launching pad for the Ironheart series also the next chapter in the Multiverse saga also a callback to Wandavision is a task as impossible as it is craven, and it left with me a pit in my stomach the size of an Infinity Stone. If Marvel couldn’t trust one of their best auteurs to make a movie without plugging their other properties, what faith could we give them as an audience?

Nearly every element of The People’s Joker is a risk. Beyond the specter of litigation, beyond the fact that it is a film with no real precedent finished on a loan, it is an incredibly intimate piece of autofiction from a transgender filmmaker. Vera performs as her pre-transition self, bleeping out her deadname except for an instance when it is thrown in her face by her boyfriend in the heat of an argument. Joker’s relationship with Mr. J is as nuanced a portrayal of a toxic relationship as I have seen, even if it is technically a love affair between two parodies of the same intellectual property. Finding someone whose experiences mirror yours can be a thrilling part of falling in love, but sometimes those matching facial scars just mean they’re gonna hurt you...really, really bad. Even as Mr. J’s behavior turns abusive, Kane Distler never plays him as a villain, and you never lose sight of the fact that he loves Joker, even as the relationship becomes untenable.

The real emotional kicker of the film is the dynamic between Joker and her mother. Here again is someone desperate to love our hero, but terrified of her growing up to be the same unbalanced, unhappy woman she knows herself to be. Lynn Downey threads the tonal needle perfectly, emphasizing the heightened mania of her character while maintaining a gripping realness that has elicited many a tear in both of the screenings I attended. Griffin Kramer plays a young Joker with a wide-eyed innocence and pain evoking Fairuza Balk’s Dorothy in Return to Oz, a film Vera has frequently cited as an inspiration. The film ends with a beautiful, complicated moment between mother and daughter that leaves the viewer feeling all of the love and pain that went into the making of such a personal film. It is adjoined by a multiversal puppet parody of silver-age DC character Mr. Mxyzptlk (that’s MX. Mxyzptlk to you!) accompanying Vera on a musical closer.

What makes The People’s Joker so compelling is that it is a film Vera Drew had to make. There is a profound affection for every institution she skewers, from comedy to comicbooks. For all of the fascist misdeeds and worse committed by this version of Batman, the film ends with a new hero redeeming the cape and cowl. It’s a funny moment, but it’s also a warm reminder that these characters are supposed to make us feel good. No matter what corporation owns them, superhero stories are important to Vera. The film is dedicated to Joel Schumacher and a pivotal early moment in her transition is watching Batman Forever and identifying less with Val Kilmer’s rubber-nippled hero and more with Nicole Kidman as his love interest. While I cannot pinpoint anything so specific (though I did dress up as a Powerpuff Girl for Halloween first at age 5 and 17), these characters are integral to who I am. But rather than rewarding you for catching all of the references to stories that have come before, The People’s Joker gets you excited for all that there is left to make. If there are still great superhero films to be created in this wasteland of a world, those that make them could stand to learn a lot from the criminal heroics of this clown princess of crime.

Excellent. I was already eager to see The People’s Joker, now, having read this, even more so. As ever, I love how you weave so many threads into one compelling narrative about both the movie in question, the state of superhero movies in general, and your journey through it all.